A history of the bread oven

The bread oven, as we still know it today, has a very long history. The “basic model” with oven floor and dome has been around for at least 4,000 years. Bread can also be baked in other, simpler ways. Man has always been inventive in his preparation of food. Depending on his lifestyle and the materials available to him, he baked bread in a clay pot on an open fire, under a movable bell-shaped vessel, or in a temporary or a fixed oven construction.

The “oven” has been around for thousands of years. Archaeologists have found remains of prehistoric ovens in many places around the world. Archaeological traces are sometimes difficult to recognise, however. Often only the substructure of the oven remains, and you do not know what the walls or dome looked like. Sometimes you still find part of the content, and you can thus determine what was baked in the oven. Because food remains do not preserve at all well, it is almost impossible to prove that an oven was used for baking bread. An oven can be used for all sorts of purposes, such as firing clay, melting metal or fat, or roasting meat.

The oldest archaeological traces of ovens date from the Neolithic Period around 9,000 years ago, and were found in Syria. In Europe, ovens around 6,500 years old have been found, for example in Rosmeer (Bilzen, Belgian Limburg). We do not know with certainty whether they were ovens for baking bread. If we consider that the oldest bread, found in Switzerland, is around 5,500 years old, we can assume that ovens were used in this period to bake bread. However, there is no real proof of this yet.

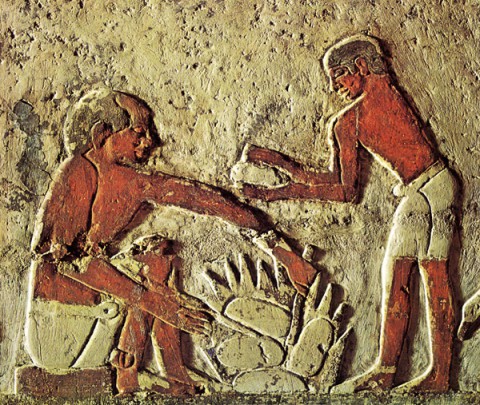

On the other hand we are indeed certain that there were bread-baking ovens in Ancient Egypt. Egyptian wooden statuettes around 4,000 years old show bread ovens and baker’s workshops with many people kneading bread at the same time. The baker’s oven is a model with a dome-shaped vault. Egyptian texts mention at least 30 different bread products, which indicates that bread was widely used and enjoyed. Baking bread was a well-organised activity that took place in real bakeries with large bread ovens. Bread was a payment in kind for the Egyptians: wages and taxes were calculated in loaves of bread.

In Belgium, traces of bread ovens can be found in houses in settlements from the Bronze Age (4,000 to 2,800 years ago) and the Iron Age (2,800 to around 2,000 years ago). With regard to the shape and appearance of these ovens, we only know that they had a circular floor with a diameter of less than 1 metre. It is generally assumed that these ovens were used for baking bread. Millstones and charred grain kernels have also been found in the houses. We are certain that the “Ancient Belgians” did bake bread around 2,000 years ago. The Roman historians mention this in their travel reports. In Ancient Gaul, “flat bread” was baked from millet, oats and barley, and sometimes wheat.

scan from DUPAIGNE B.: p. 45.

Baking under a baking bell or an overturned receptacle is described by Roman agriculturists (“sub testu”). In many parts of the empire, small ovens or baking bells were used in which just one or two loaves were baked. In the Roman vicus at Velzeke (East Flanders) such a mobile bread oven was found that dates from the first century A.D.

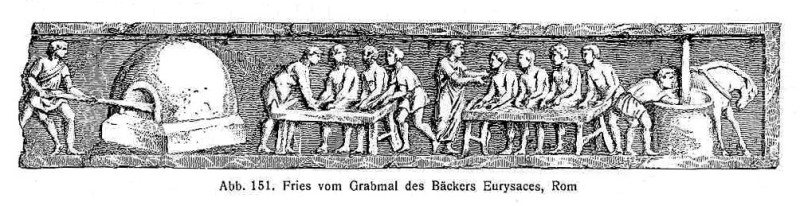

Large bakeries emerged in all Roman cities and had professional bread ovens where a lot of bread could be baked at once. This was undoubtedly also the case in Belgian cities such as Tongeren. Archaeologists often find traces of enormous grain barns (the horrea) on the edges of these cities, generally on the banks of a river or along a connecting road.

Roman bread oven, part of a frieze of the monument to the baker Eurysaces, Rome, 1st century B.C.

scan from BRANDT P.: p. 117.

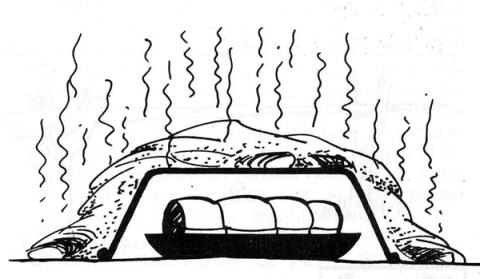

baking under a bucket (Sub Testu)

Up until 100 to 150 years ago, a lot of cooking was done on an open hearth. If a person was running out of bread and it was not yet baking day, he could bake an extra loaf of bread. Naturally, he did not want to heat up the oven just for one loaf. The coals and ash were removed from the middle of the hearth floor, the dough ball placed on it and covered with an overturned stone pot (in the garden you can use a steel bucket). The hot coals were then put over it. This ancient baking method was described around 2,000 years ago by a Roman agriculturist who called it “sub testu” baking.

Another method for baking an extra loaf is to use a small sheet steel oven that can be put on the stove or the gas cooker.

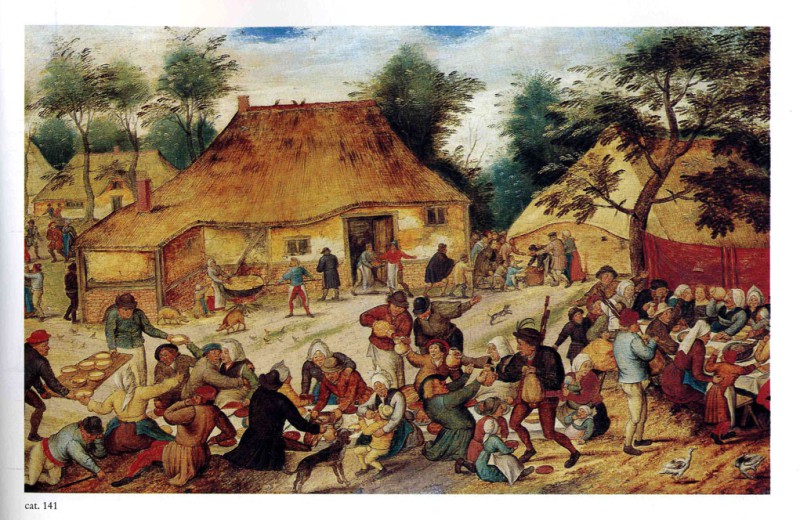

During the Middle Ages there was an increasing specialisation and more and better bread was baked: every country, region or city had its own characteristic baking products. Flanders was mainly known for its delicious flans. The city bakers were organised into guilds and enjoyed considerable esteem. They were subject to strict rules and the bread price was set by law.

The situation was completely different in the country. Peasants grew their own grain and generally baked the bread themselves. The large farms often had their own bakehouse. The smaller farms had their self-made dough baked in a communal bakehouse that belonged to a group of neighbouring farms. They could also have their pre-risen dough baked in the local landlord’s bakehouse, against payment in kind. Some farmers took their grain to the city to have it baked by a “contract baker”.

Every Middle Age monastery or abbey had its own bakery where large quantities of bread were baked. It was not just for their own consumption. Monasteries were required to give bread to travellers, the poor and the sick. Supplies for many pilgrims also made the monasteries large bread producers. This is shown by, among other things, the number of grain mills owned by the monasteries. Each monastery owned a number of mills that were spread over a number of large farms. This was the case in Grimbergen for example: both the Liermolen and the Tommenmolen, two sections of the Museum of Old Techniques, were owned for centuries by Grimbergen Abbey. Only with the French Revolution (1795) did they revert to private ownership.

scan from Pieter Breughel de Jonge (1564-1637/8) - Jan Brueghel de Oude (1568-1625). Een Vlaamse schildersfamilie rond 1600: p. 389

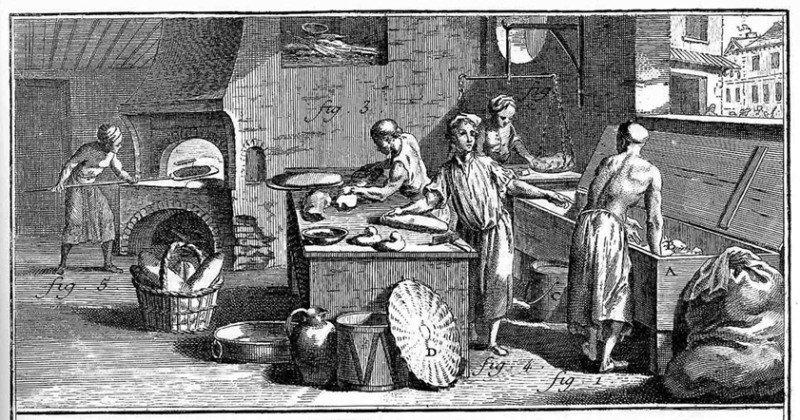

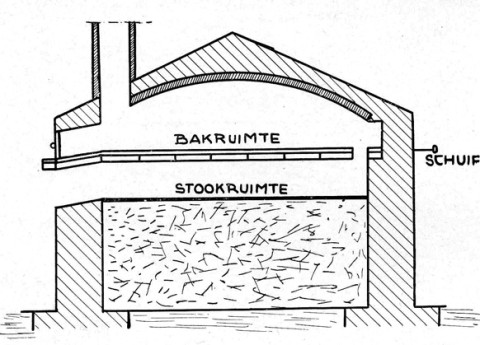

Around 1900, people in cities generally bought their bread from a baker or from a “bread factory”. Large industrial bakeries emerged at the end of the 19th century, some in the form of co-operating companies. They had a number of large ovens that were heated with coal or by a web of steam pipes. Kneading machines were used to knead the dough. The principle of “indirect” heating was used in these industrial ovens, with hot air or water. The bread was baked in a separate area, detached from the actual heating area. This made the use of coal - which produces noxious gases - possible. Baking could also be done without interruption, which meant substantial time savings. Production increased while fuel consumption fell.

In the country on the other hand, baking was still mainly done at home in 1900, in ovens for 15-25 loaves that were heated with wood. The gas oven or electric oven did not yet exist at the time. By no means everybody had a bread oven. They were mainly found in the larger farms. Baking was done once a week.

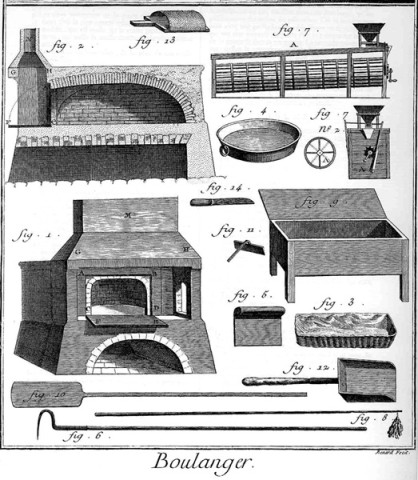

scan from BROCX W.L.: p. 20

If you did not have your own oven, you could have your bread baked by a neighbour or in a communal oven. There was often such a bread oven in villages and they were generally located in the village square. You can see one at the village square in Duisburg (Flemish Brabant).

There was also often a bread oven in the local train station or in the “level-crossing operator’s home”. Most train stations had such bread ovens in the periods 1880-1890 and 1926-1930. You could also take your leavened dough balls to a baker to have them baked. In Belgium’s famous Ons Kookboek, published by the Belgische Boerinnenbond (i.e. a cookery book of the Farmer’s Wives Association) in 1949, there is still a mention of baking at the baker.

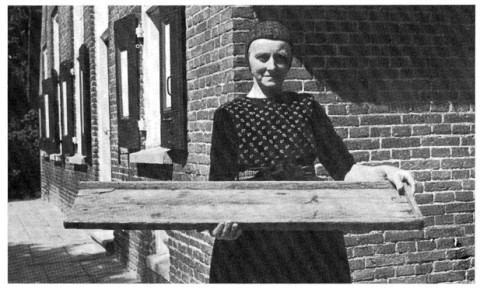

If you had your bread baked in a communal oven or by a baker, you generally placed an identification mark on the bread. It was often done with a bread stamp pressed into the dough.

scan from RIETVELD AD.: p. 43.

making a bread stamp

If you want to bake bread together with your neighbours, then it is useful to distinguish your own bread from that of the others. You can just cut a sign in each dough ball, but it is nicer to use your own bread stamp.

You can cut one from wood, as Georges Van Laer did for the MOT.

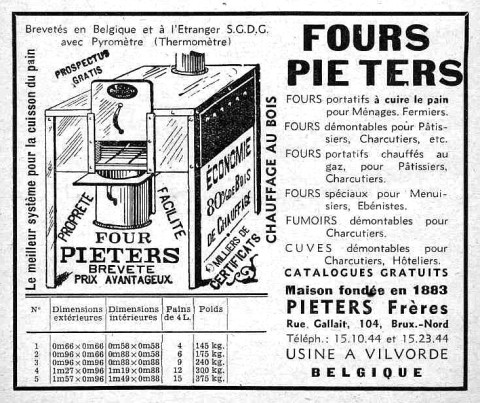

At the start of the 20th century, ready-made metal bread ovens were also sold, for example by the Pieters company in Schaarbeek. These simple metal constructions were only suitable for small-scale baking, of a maximum of 10 loaves. The customers were urban middle-class families. According to Pieters advertising, the success of this type of oven was mainly due to the ever increasing practice of “doctoring bread”, where bakers used lower quality ingredients or falsified the weight.

In Belgium, private bread ovens and bakehouses were still built in the country even during the Second World War. After the Second World War, bread was increasingly sold in bakeries or delivered to the home by the baker. If bread was still baked at home, it was done in a “modern” gas oven or electric oven. Baking bread on stone became increasingly rare and has now almost completely disappeared.

Elsewhere in Europe however, home baking on stone continues. This is especially so in the poorer regions where people live solely off farming. In large parts of Romania, Hungary and the rest of south-east Europe bread is still baked at home in baker’s ovens and bakehouses.

scan from GIELE J.: s.p.

baking in the Middle East and North Africa

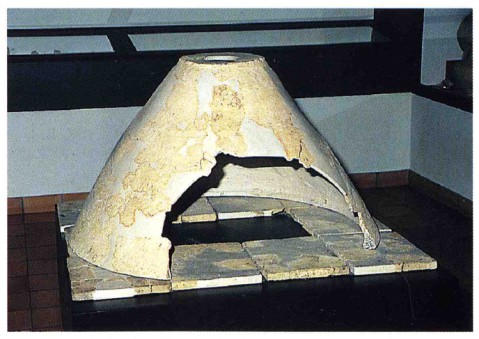

In the Middle East and North Africa, smaller ovens are used where “dough disks” rather than dough balls are baked. They are not put on the oven floor, but stuck to the inside of the dome. The floor is only used for heating.

Scan from MACHEREL C., ZEEBROEK R: p. 97